Engagement, innovation & inclusive development

Our starting point*

Publicly-funded universities and science institutions in South Africa are mandated to engage with communities.

In the mid-2000s, a strong policy push for South African universities to engage with communities in their local settings emerged. This was partly a reaction against growing industry influence on research, but also to ongoing and widespread poverty, inequality and unmet socio-economic needs. The policy push for science councils and other types of science institutions to engage and address development needs at the local level is more recent. The need for publicly-funded research and innovation to be more inclusive of the needs and capabilities of people in resource-poor community settings has been given renewed emphasis in the 2019 White Paper on Science, Technology and Innovation, for example.

*Contact Dr Il-haam Petersen (ipetersen[at]hsrc.ac.za) or Dr Glenda Kruss (gkruss[at]hsrc.ac.za) for more information about this project.

We chose to work with communities in three provinces in South Africa: Carnarvon (Northern Cape), Cofimvaba (Eastern Cape), and Philippi (Western Cape). Scroll to download the visual storytelling booklets from each case study.

Our questions

When it comes to research and innovation, communities are very typically involved as recipients of one-directional flows of knowledge from “experts” based in universities, science councils and other institutes of science. In this mode of practice, communities are included as passive beneficiaries, and engagement can become exploitative and primarily to the benefit of the university, science institution or the individual student.

So, how can universities and science institutes engage with ‘communities’ to mutual benefit?

With funding from the National Research Foundation, the Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators started a project in 2017 to explore ways for universities and science institutions to better engage at the community level and contribute more to change in their local settings.

Two key questions we aimed to address were:

- How can academics and researchers make the knowledge they produce more useful at the community level?

- How can we get people in communities to use this knowledge more, to improve conditions in their communities and to build their livelihoods?

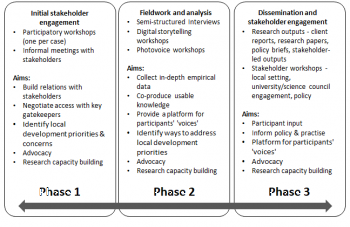

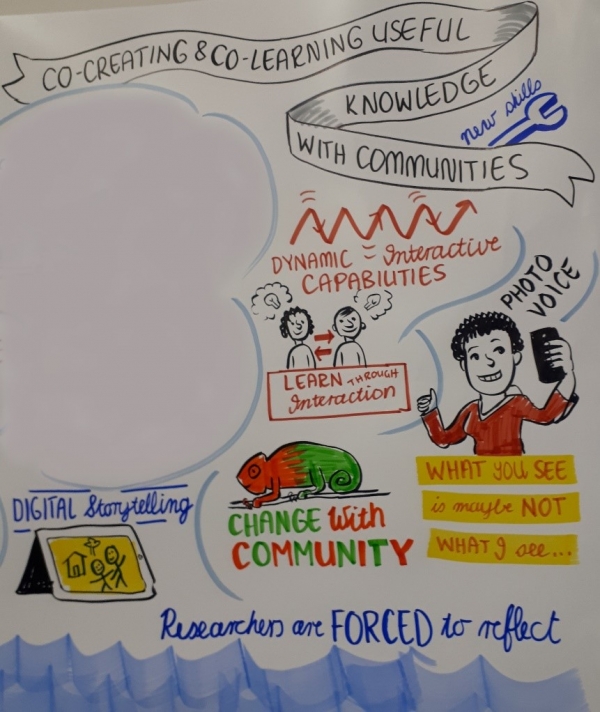

Defining dynamic interactive capabilities [Source: Illustration based on the project presentation at the 2019 SAHECEF Conference, 4-6 December, Nelspruit, Mpumulanga]

What do we mean by engagement?

Over the past decade, there has been much deliberation about exactly what ‘engagement’ means and who should be engaged. It is increasingly agreed among academics and researchers that:

Engagement between academics, researchers and communities should be about ‘extending knowledge resources’. It is not an activity that academics engage in as citizens, nor is it an ‘add-on’, but is core to their disciplinary commitments and identity as academics.

Engagement that is mutually beneficial is about learning from and with communities:

Gemeenskapsbetrokkenheid = werklike interaksie, luister en hoor [Community engagement is about ‘real’ interaction and active listening] Saam dink en saam luister…na toepaslike oplosings [Thinking and listening together ... towards appropriate solutions] - (Bibi Bouwman, SAHECEF, 24 March 2018)

Capabilities to engage and learn through interaction is crucial

Implementing this kind of engaged scholarship approach in practice, at the institutional and individual academic level, has been a major challenge. There is an emerging body of literature showing that universities and science institutes require specific capabilities to produce knowledge that is useful and useable. Similarly, community-based actors require the capabilities to interact and use formal knowledge to address their development concerns.

We argue that the capabilities to keep up with change and learn through engagement are crucial. This set of capabilities have not been given much attention in the literature, in policy or in practice. We call these dynamic interactive capabilities (based on the work of Nick von Tunzelmann (2010)).

Building local capabilities to facilitate mutually beneficial engagement

Building relationships that take into account the agency of community partners across unequal knowledge and power divides is challenging. This challenge is now increasingly recognised, albeit on a small scale, and has become evident in more recent experimental initiatives to facilitate knowledge flows. Examples include township-based science shops, or technology platforms catering for SMMEs and co-operatives, as well as numerous initiatives within the education, health and environmental domains.

A key focus for this project was therefore to understand the conditions that facilitate and constrain ‘communities’ to work with universities, science councils, big science projects and other science institutions, and to use their knowledge resources to address their developmental needs. Specifically, what capabilities do ‘communities’ require to seek out and use formal knowledge to innovate and improve their livelihoods? And how can we – i.e. universities, science institutions, government, civil society, community-based actors – support the building of such capabilities?

From the start of the research, we decided to go beyond exploring what exists, to try to build a picture of possibilities for engagement with more long-term benefit to the select local communities. We argue that building local capabilities, for production and innovation, is one important way for universities, science councils and other science institutes to contribute to addressing development needs in their immediate surroundings. The research project thus adopted the local innovation and production systems (LIPS) approach, developed by Jose Cassiolato and Helena Lastres at RedeSist in Brazil, as a guiding framework.

Studying engagement in three local settings

The SKA and the hospitality industry in Carnarvon, a remote town in the Northern Cape

The first case study focusses on the community of Carnarvon in the Northern Cape, and its interactions with the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) telescope, which hosts an infrastructure site near the town. Carnarvon is the closest town to the SKA site in the Karoo. This big budget global science project has presented significant challenges as well as opportunities for development in the town. Over the years, there has been an increase in visitors to the town – mainly people who work for or with the SKA such as technicians, engineers, civil servants and scientists rather than leisure tourists. Not long after the SKA rose to prominence in the consciousness of the local public, enterprising entrepreneurs began to react to the promise of new markets. B&B’s were upgraded and expanded. New B&B’s opened up. Restaurants opened doors or expanded seating. Suppliers benefitted as new sources of revenue made their way through local supply chains. However, the sector faces many challenges, including limited access to capital, limited knowledge and capabilities, constrained access to networks, and racial imbalances in ownership and employment.

Potential of ICTs for rural development in Cofimvaba, a rural town in the Eastern Cape

Cell phones, tablet technology, the Internet, wireless networks, and other information and communication technologies (ICTs) are seen as critical technologies that universities, science councils, community-based organisations, NGOs and the public sector generally can support to promote inclusive development in rural villages such as Cofimvaba in the Eastern Cape. A particular focus has been in schools, to provide young people with the digital tools required in the economy, for example. A challenge is that few ICT initiatives aimed at addressing development needs (ICT4D) in the Eastern Cape have contributed to building local business. As a result, people in the local communities, even those who are beneficiaries of ICT4D initiatives, have few options to turn to when digital devices breakdown, for support with regular maintenance, and for skills training to support future planning and as the need arises. ICT4D initiatives, including those lead by universities and science councils, thus tend to have limited impact in the long-term. An important question that the second case study aimed to address is, how can we promote ICT4D in a way that is more likely to contribute to building local capabilities? Mutually beneficial engagement at the community level is central to this.

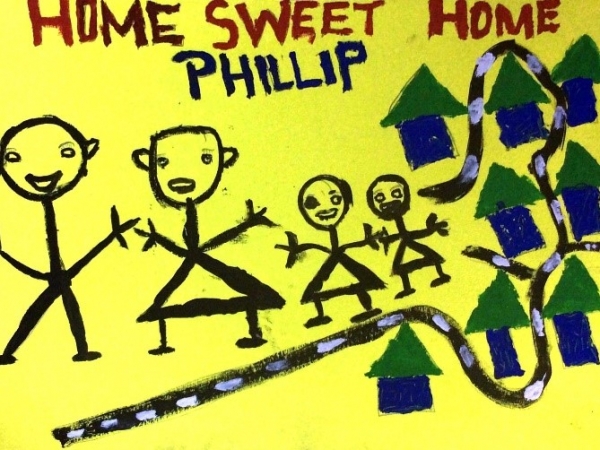

An innovation hub in Philippi township in the Western Cape

In 2016, the University of Cape Town’s Graduate School of Business established the university’s first community-based campus facility at a township innovation hub in Philippi, one of the oldest townships in Cape Town. Community-based hubs are emerging as useful mechanisms for bringing the university closer to communities, physically and in orientation. The third case study focused on the interaction between the innovation hub and the surrounding community. Like other large townships, Philippi is an under-serviced area with high unemployment. The main aim of the Philippi Innovation Hub was thus to nurture micro-enterprises and small-scale entrepreneurs, support skills development and promote job creation. A challenge for traditional knowledge actors like universities is that conventional training, incubation and support programmes based on formal knowledge transfer models may not be unsuitable. They may exclude the majority of informal businesses, which tend to be survivalist enterprises.

Working in an engaged way

When we started the research in 2017, we knew that we had to design the project in such a way that would allow us to conduct the kind of engaged research we were advocating. We had to practise what we were preaching! We thus adopted a participatory approach (see Figure 1).

Engaging our stakeholders from beginning to end

“Die gemeenskap is almal van ons.” (Bibi Bouwman, SAHECEF, 24 March 2018)

The HSRC teamed-up with the South African Higher Education Community Engagement Forum (SAHECEF) to host workshops and other advocacy events designed to get academics, researchers, students, policymakers in government, NGO workers and representatives from community-based organisations to discuss and identify practical ways to bridge the divides between them.

The research began with a set of initial stakeholder engagements that informed the focus of the case studies, and the research design and methodology. In 2017 and 2018, we conducted three initial stakeholder workshops, one in each of the local settings of the case study research: Philippi (7 November 2017), Carnarvon (14 March 2018) and Cofimvaba (24 April 2018).

Through the workshops, we aimed to ensure that the case study research addressed practical questions important for the local setting of each case study. The discussions were analysed and used as a guide to decide on the focus of the case study research and the research methods. The community-based actors in each of the local settings wanted platforms for their voices to be heard and taken seriously.

“We’ve been living here all our lives. These are the issues. Just listen to us.” (Workshop, 24 March 2018, Carnarvon)

Co-learning and co-producing research outputs

The project team tried to find suitable research tools that would enable the inclusion of community members’ voices in our research, and searched for ways to provide platforms for community members to convey their messages. This search brought us to techniques commonly used in community development and that involve storytelling through video clips and photo-stories: digital storytelling and photo-voice.

Because these methods provide useful tools for engagement, they are becoming popular in research. The value of digital storytelling and photo-voice is that they provide useful tools for co-learning and co-production – two importance processes for engaged scholarship.

Photo-voice with community-based actors in Carnarvon, Cofimvaba and Philippi

Photo-voice enables people to represent and bring recognition to the places where they live and their priorities for change, by taking photographs and reflecting on them. Photo-voice is a powerful visual method for conveying people’s experiences, opinions and messages. We call these photo-stories.

Through intense workshops over three-to-four days, our team worked with groups of people in Carnarvon, Cofimvaba and Philippi to co-produce three sets of photo-stories. What do we mean by ‘co-produce’? The photo-stories were captured through a workshop process facilitated by the research team. They reflect the participating community members’ experiences, opinions and advocacy messages that relate to a specific guiding question. We compiled a set of booklets to share the photo-stories.

Download booklet(s): Carnarvon | Cofimvaba | Philippi

The photo-stories provide insight into the lived realities of people in Carnarvon, Cofimvaba and Philippi who are trying to make a living and take up opportunities to better their lives and the lives of others in their communities.

The booklets describe our attempt to engage and co-produce research with individuals at the community level. Each booklet includes a specific recommendation or set of recommendations conveyed by the community members to academics, researchers, policymakers and decision makers in their communities.

Dissemination as part of a participatory process

Stakeholder engagement and photo-voice exhibitions

The research process emphasised stakeholder engagement and ended with a set of stakeholder consultation meetings and workshops. The photo-stories were shared through exhibitions held as part of these workshops.

Final project workshop, Boosting Carnarvon's hospitality sector: role-players and opportunities, held on 4 November 2019 at the Kareeberg Library in Carnarvon [Source: HSRC/CeSTII]

Final project workshop, Township Innovation Hubs: opportunities for building local capabilities and opening up new trajectories, held on 14 November 2019 at the Solution Space Philippi, UCT Graduate School of Business, in Philippi [Source: HSRC/CeSTII]

Final project workshop, Enhancing the potential of ICT4D in the Eastern Cape: role-players and opportunities, held on 26 November 2019 at Radies B&B and Conference Centre in Cofimvaba [Source: HSRC/CeSTII]

Digital storytelling with informal business owners in Philippi

In 2018, the HSRC team collaborated with the Sustainable Livelihoods Foundation (SLF) to co-facilitate a digital storytelling workshop with participants from Philippi township. This was part of our experimentation with using participatory visual methods to investigate innovation and knowledge flows in informal settings.

Through an intense 5-day workshop, the team worked with seven informal business owners from Philippi East to produce a set of short video clips describing their lived realities of entrepreneurship in the township. The digital stories provide insight into the challenges they face and how they have used innovation to overcome these challenges.

The stories highlight knowledge needs and show how informal business owners address their knowledge needs. Through these stories we were able to gain an understanding of the roles that universities and science institutions are playing and could play in a township setting. The stories also indicate the role of other types of education and training providers including NGOs.

Digital stories by informal businesses in the services sector in Philippi East

Story 1. The start of S.N. Clothing

About the informal business owner: Sylvia lives in Hazeldean, Philippi. She is 49 years old and a mother of four children. She worked at a company called Vollenhoven Fashions where she developed useful skills. On 12 April 2015, she decided to start her own business. [Source: HSRC/CeSTII, Sylvia]

Story 2. Backward ever, forward ever

About the informal business owner: Richard is a father of two children. He is from Zimbabwe and now lives in Philippi, Cape Town. He is a street vendor operating from an open space in front of Philippi Mall. Richard is looking forward to expanding his business…to be big! [Source: HSRC/CeSTII, Richard]

Story 3. Spinach story

About the informal business owner: Enesia is 35 years old. She is a mother of two children and is from Zimbabwe. She lives in Philippi, Cape Town, where she is running a business. Her business is growing and she can now manage to send her children to good schools. [Source: HSRC/CeSTII, Enesia]

Story 4. In this world

About the informal business owner: The business owner opted not to provide a biography. [HSRC/CeSTII]

Story 5. Long life to freedom

About the informal business owner: Stella is a very strong and intelligent woman. She says, 'I have big dreams and I live it, but would like my dreams to become more successful'. Stella wants her family to live happily, and her children to have a better education and a better life. This motivates her to work even harder. [Source: HSRC/CeSTII, Stella]

Story 6. The beginning of Dila's Corner

About the informal business owner: Grace describes herself as 'South African born and bred', and a woman who can't just sit back and complain about what is happening around her. One of her strengths is that she is able to accommodate and adapt to different cultures. 'South Africa is a rainbow nation’. [Source: HSRC/CeSTII, Grace]

Story 7. Mama Chicken

About the informal business owner: Ma Kheswa has three children and she lives in Philippi. She has a small business selling chicken and eggs. 'I want someone to help grow my business. My child is finished Grade 12. She wants to study at university but we don't have money. [Source: HSRC/CeSTII, Ma Kheswa]

A partnership for impact

This project was led by the Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators (CeSTII) in collaboration with the Education and Skills Development (ESD) research programme at the HSRC.

The HSRC team collaborated with four strategic partners to strengthen the quality and impact of the research:

- Advocacy partner: South African Higher Education and Community Engagement Forum (SAHECEF). Together, we hosted eight interactive workshops and seminars in Philippi, Cofimvaba, Carnarvon and Sweetwaters – and thus engaged stakeholders in four provinces in South Africa.

- Capacity-building partner: Bertha Centre for Social Innovation based at the University of Cape Town’s Graduate School of Business. A total of fifteen NRF-bursaries were allocated to students registered in the Master's in Inclusive Innovation programme over the three-year period, 2017 to 2019. The students’ research covered a range of topics related to inclusive innovation such as how micro-property developers in townships can attract impact investors, and the impact of mobile technologies on scaling informal, female-owned street vendor businesses.

- Case study research partner: Prof. Mogege Mosimege, Professor and Head of the School of Mathematics, Natural Sciences and Technology Education at the University of the Free State (UFS). Prof Mosimege led the case study team exploring the role of universities and science councils in supporting the use of ICTs for rural development in Cofimvaba in the Eastern Cape.

For more information, contact Dr Il-haam Petersen (ipetersen[at]hsrc.ac.za) or Dr Glenda Kruss (gkruss[at]hsrc.ac.za).