Financing BRICS climate change action: Cities as nuclei for implementation

DATE: 6 December 2019

AUTHOR: Andrea Teagle

Cities are well positioned to respond to climate change, as decisions can be undertaken reasonably rapidly, and have direct and non-tangible implications. In a recent HSRC seminar, Kamleshan Pillay of the C40 cities climate leadership group, joined the HSRC’s Babalwa Siswana and Krish Chetty in exploring the policies of cities across the BRICS countries, and how these responses have been shaped and restrained by national policies. Their upcoming research outlines how cities might drive climate action going forward.

Cities are increasingly being recognised as important nuclei for climate change mitigation and adaptation responses. As centres of population and economic growth, they often bear the brunt of the impacts of climate change, and are thus directly incentivised to drive adaptation and mitigation projects. And as comparatively small units, they are better able to react quickly and flexibly than national governments.

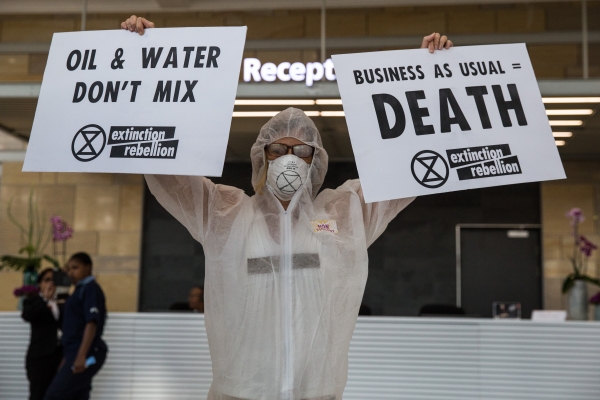

Climate change activists protest outside the Cape Town International Convention Centre during Africa Oil Week, 5 November 2019.

Photo: Ashraf Hendricks/GroundUp (CC BY-ND 4.0)

“There’s a natural direction to use cities as a lens for understanding how to enable greater renewable energy implementation,” said Kamleshan Pillay, the adaptation finance manager of the C40’s Financing Sustainable Cities Initiative speaking at a recent HSRC seminar about the role of cities in reaching climate change targets.

The BRICS countries – Brazil, Russia, India, Shina and South Africa – remain heavily reliant on fossil fuels. South Africa and Russia, in particular, have an abundance of fossil fuels and very little green energy infrastructure, making the switch to greener energy at a national level a costly undertaking. Brazil is the only country within BRICS that mostly uses green energy – hydro-electricity – and yet is still one of the world’s greatest greenhouse gas emitters due to largescale Amazon deforestation.

However, cities across the BRICS countries have achieved some climate action successes. In an upcoming publication, Pillay and HSRC co-authors Babalwa Siswana and Krish Chetty interview BRICS cities to explore potential avenues for green technology funding.

Their findings indicate notable progress in adaptation and mitigation in the transport sectors (except for South Africa), waste, and lighting in commercial buildings through green building certification standards.

But cities face various challenges in implementation.

The primary challenge is a lack of alignment between city-level and national policies. While the major BRICS cities have set emission-reduction targets, there is still an absence of enforcement measures under international climate policy, Pillay said.

Lack of funding

There is also no provision for cities to access international funding for climate action directly, and as a result, cities are constrained by national policies.

“The problem with the Green Climate Fund, for example, is that there’s no direct access clause, which means cities still have to go through national accredited entities,” Pillay explained. “If there’s a lack of political will at the national level, they won’t apply for the climate funds.”

BRICS cities have tended to stay clear of issues falling under national jurisdiction, such as water management, and have instead focused on measures that can be indirectly financed – for example, reductions in emissions in the transport sector through consumer-based incentives and multi-passenger policies.

For cities to widen their scope of implementation to begin a meaningful shift to renewable energy resources requires large capital injections. This kind of investment is hampered by long payback periods and political uncertainty, Pillay said.

In South Africa, renewable energy investments require 20-year power purchase agreements, which investors are shying away from in light of the uncertainty around the Renewable Energy Independent Power Producers Programme and the integrated resource plan – which was finally updated in October this year.

Elephant in the room

South Africa and Russia both have an abundance of fossil fuels which make the switch to renewables at scale very difficult. India is also reliant on coal, but has a sizeable green energy sector, with 34% of energy coming from renewable energy, Siswana said.

Despite the substantial potential for solar, hydro and wind energy, 91.2% of South Africa’s electricity is generated from coal. South Africa aims to increase its renewable energy contribution from 8.8% to 30% by 2030.

Pillay pointed to ongoing coal subsidies as a key issue. “The elephant in the room are the provisions for fossil fuels through subsidies which means that coal may last longer as an energy source than it should, and ultimately lead to us to missing our 2030 emission reduction target.”

Deteriorating existing infrastructure has meant that the state is scrambling to meet current supply in ways that are not necessarily optimal for the long-run. For example, investments in natural gas – while an improvement on coal– would be better channelled into greener alternatives, Chetty suggested.

The need to invest in infrastructure with a long-term outlook is underscored by some of the challenges that Brazil is currently facing. While most of the country’s energy is produced by hydropower, changing weather patterns are threatening its green energy profile. In São Paulo, for example, Siemens is supplanting hydropower with ethanol from sugar cane to drive steam generators, Chetty said.

However, Brazil’s investments in renewable energy sources have declined sharply since the election of President Jair Bolsanaro in 2018.

China is the most controversial performer, Chetty said, as both the world’s biggest greenhouse gasses emitter and the biggest investor in green technology. China outspends all of the Western countries in renewables, although investment reportedly dropped significantly in the first half of 2019.

Since 2013, China’s fossil fuel dependency has dropped slightly in favour of renewables. However, China continues to fuel coal plants, as well as green energy projects, in other parts of the world. South Africa is one of the major recipients of coal energy funding.

One cause for optimism, according to Pillay, is that multilateral development banks, including the World Bank, are starting to move away from financing fossil fuel energy production. In August, Standard Bank joined Nedbank and First Rand in refusing to fund independent coal power producers (although the bank stated that it would still support ‘clean’ coal, a term slammed by environmental groups).

Such shifts might begin to steer countries towards greater use of renewable energy. In South Africa, simplifying regulations to expand small-scale electricity generation might help to accelerate the shift to renewables, the researchers said.

SA leads in adaptation initiatives

While falling behind on reducing emissions, South Africa has implemented the most adaptation measures among BRICS, followed by Brazil.

This has been made possible by access to multilateral climate donor agencies. The extent of adaptation measures also reflects Southern Africa’s comparatively greater exposure to various climate hazards.

In addition to protecting citizens, cities are compelled to put into place measures to protect energy infrastructure from climate hazards and to maintain development gains. However, the report indicates that the major BRICS cities remain largely reactive in their approaches, responding to climate hazards when they occur.

According to Pillay, there is a need across BRICS cities to invest in more measures to adapt to extreme heat, particularly because of the urban island heat effect (where insulation from building materials and heat generated from daily activities in cities contribute to higher temperatures than in surrounding rural areas).

Once the report – Evaluating the climate policy and RE implementation alignment of BRICS cities with national mandates – is published, the authors hope that it will act as a lobbying document for the BRICS coalition, and help to remove some of the barriers that cities face in bridging the implementation gap.