Dissatisfaction with government's anti-corruption efforts linked to voter abstention in 2019 elections

DATE: 25 June 2019

AUTHOR: Andrea Teagle

Residents of Bathurst and Nolukhanyo in the Eastern Cape take part in one of several anti-corruption protests in South Africa in 2017.

South Africans have increasingly viewed corruption as one of the major issues facing the country. Data from the Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS) presented at a HSRC seminar this month indicates that, while perceived corruption did not impact intention to vote in the last elections, dissatisfaction with the government’s anti-corruption efforts did. Rebuilding public trust, critical to the workings of democracy, will require the prosecution of corrupt senior officials, speakers argued. By Andrea Teagle.

In 2017, at the end of Jacob Zuma’s second term in office, a record 30% of South Africans named corruption as one of South Africa’s greatest challenges. This is up from just 9% in 2003, according to the HSRC’s Dr Benjamin Roberts, speaking at a recent HSRC seminar, Perceptions of Corruption and the 2019 elections.

Presenting findings from the latest Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS), Roberts noted that the surge in public concern over corruption over the past 16 years represents a convergence of public and expert perception of corruption. In 2018, however, the proportion of South Africans who named corruption as a major concern dropped to 23%, suggesting cautious optimism about corruption under President Cyril Ramaphosa’s regime.

Perceptions of corruption were linked to dissatisfaction with democracy in South Africa, according to the SASAS results. Roberts said that among South Africans who indicated that they were satisfied with government’s anti-corruption efforts, two thirds (67%) were satisfied with democracy; compared with less than a third (29%) of those who reported being dissatisfied with anti-corruption efforts.

“The perception is that either… the failure of our other democratic institutions is giving rise to corruption, or massive corruption is giving rise to the failure of our institutions,” said fellow speaker David Lewis, executive director of Corruption Watch. “I think that both are true by now.”

How does the increase in perceived corruption impact voting attitudes and beliefs?

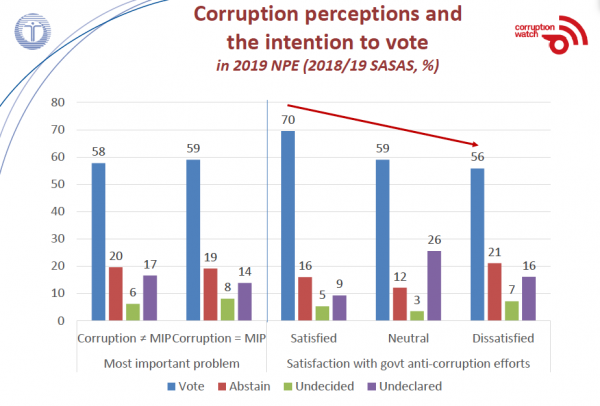

The most recent iteration of SASAS revealed that, contrary to speculation prior to the 2019 elections, concern over corruption had no impact on voting. South Africans who named corruption as a most important issue were no less likely to report registration, or to express intention to vote, than those who did not, Roberts said. The survey also showed a widespread belief that citizens had a duty to vote that was not affected by perceived corruption.

However, the intention to turn out was linked to reported satisfaction with local government’s efforts to tackle corruption. Just 56% of dissatisfied individuals intended to vote, compared with 70% of those who were satisfied with anti-corruption efforts, Roberts noted. This perhaps reflects the public’s desire to see improvements in their own localities that are currently hindered, or perceived to be hindered, by corruption. Indeed, Lewis noted that poor service delivery is widely believed to a result of corruption.

SASAS also asked respondents about how they express dissatisfaction with their party’s performance through voting.

Data from 2018/2019 showed that South Africans – regardless of whether they fell into the corruption-worry camp or not – are primarily loyalists. Half (51%) of those who didn’t name corruption as a major concern indicated that, in the event their party did not meet their expectations, they would give their party another chance, or wait for an explanation and then decide. This figure was only slightly lower for the corruption-worry camp, at 45%.

However, among respondents dissatisfied with party performance, abstention was notably higher among those concerned with corruption (28% versus 22%).

That perceptions of corruption in turn impact the workings of democracy by reducing voter turn-out emphasises the importance of rebuilding public trust in state institutions. Advocate Gary Pienaar, senior research manager at the HSRC’s Democracy, Governance and Service Delivery programme, noted that the three main parties all campaigned with anti-corruption promises, eyed warily by an electorate largely disillusioned with anti-corruption efforts. (The percentage of respondents indicating satisfaction with efforts to tackle corruption has bobbed around 24% since 2012.)

Political analyst Khaya Sithole argued that the EFF’s performance was disappointing given a manifesto centred on issues affecting young black South Africans, and suggested that the anti-corruption promises of the EFF– as well as those of the ANC and DA– were undermined by the lack of consequences faced by corrupt senior officials.

Deputy President David Mabuza’s move to put himself before the ANC’s toothless integrity commission at the last moment was merely another ploy to win over the public, said Pienaar.

“Given what we know in the public domain about the allegations against the deputy president, it's difficult to see how he could conclusively clear his name before a detection commission that reportedly has no structure, has no resources, and certainly has no ability to undertake a proper hearing.”

Thus, despite the slight upturn in public concern about corruption that accompanied former president Jacob Zuma’s exit from office, the Ramaphosa administration has its work cut out for it to rebuild public trust. Lizette Lancaster from the Institute for Security Studies argued that this would require successful prosecutions of corruption cases, noting that the National Prosecuting Authority’s (NPA’s) low conviction rate was partly due to lack of critical skills. The NPA is currently operating with a vacancy rate of around 20% due to austerity measures, she said.

In addition, unrealistic conviction rate targets have given rise to selective prosecution strategies, where the NPA selects cases that they feel they have a chance of winning. The result is that the more complex cases, including corruption cases, are often left off the role.

However, Lancaster said that there are renewed efforts underway to motivate for greater funding, and to rejuvenate the NPA. “What has been encouraging is that we have seen efforts in the criminal justice system, most notably with the appointments of leadership in the hawks as well as the NPA.”