Lessons from Cape Town's Day Zero: Residents are willing to cooperate but need clear communication and sustained engagement

In January 2018, the City of Cape Town’s water supply dam levels dropped to 28%. It was the lowest in a century of rainfall records. The city declared Day Zero and stringent water restrictions, which mobilised Capetonians to reduce their water consumption sufficiently to stave off disaster until the winter rains came. An HSRC survey revealed how households, businesses and organisations conserved water during the water crisis and how people experienced the impact of the drought differently, depending on their income, age and location. The findings will inform policy dialogues and an HSRC policy brief.

At the end of the 2017 winter season, the City of Cape Town’s water supply dam levels stood at a mere 38.5% compared to 78.4% the previous year. The dams depend on winter rain to be replenished, but the levels were the lowest in 100 years of record keeping. December’s dry summer festive season lay ahead and it was unlikely to rain for months.

Cape Town is a prominent international tourist destination, but during its dry summer season, the region also sees an influx of domestic holiday makers for the December school holidays, with increased water consumption.

The City issued warnings and alerts, but residents and businesses did not reduce their water consumption significantly. By January 2018, dam levels had dropped to 28%. At prevailing consumption rates, Cape Town’s water supply would have been depleted by 16 April 2018, a date which the City declared as Day Zero. Water restrictions were lowered to 50 litres per person per day and the City established an online dashboard to keep residents up to date about dam levels.

Consumption dropped and Day Zero was averted, but in many households, buckets stayed in showers, even months after the winter rains came. In wealthier suburbs, grey-water systems and water tanks continue to signal a certain virtue.

In hindsight, it is easy to criticise the local and national government for its handling of the crisis, but researchers and the authorities realised that the lessons learnt needed to refine future disaster management protocol. To this end, the HSRC embarked on a survey between January and March 2019 to find out how Capetonians conserved water and adapted their habits in response to the drought.

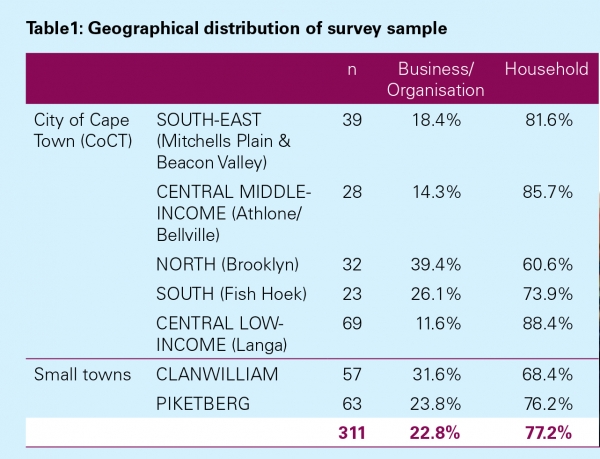

Researchers conducted in-depth interviews with government officials about the management of the crisis and surveyed seven areas across the Western Cape.

Of the 311 responses, 77.2% were from households and 22.8% from businessness and organisations.

Resilience and impact

A relatively large proportion of low-income respondents in the Langa township (14.5%) reported that the drought had “no impact at all” on them. Another 31.9% reported “a small impact”. The researchers believe this reflects the resilience that poorer people have developed in their daily lives. Households and businesses in that area are familiar with frequent walks to fetch water at communal taps and the water saving and recycling activities necessary for survival.

People aged 30 years and older were more likely than the younger people to indicate that the drought had a considerable or major impact on their lives. This suggests that the age group most likely to be home or business owners were more likely to be aware of the drought and the associated punitive tariffs on their lives.

The most serious effect was in respect of hygiene and household duties (29%), gardening (16%) and a financial burden (10%). Behaviour changes included taking shorter showers, reusing bath water for reuse, catching grey water and reducing laundry routines and cleaning activities.

Costly water installations

A small proportion of respondents provided data on their water consumption, which showed the average domestic household water usage declined by 50% from 16.82 litres per month in 2016 to 8.94 litres in 2018. Higher-income respondents mitigated the impact of the drought by installing water tanks, boreholes, purification systems and related infrastructure to secure off-grid water supply. These installations became a significant talking point and a matter of pride for the respondents. However, the cost was totally beyond the budget of the low-income respondents, who used other ways to reduce consumption, as one woman explained:

“We used bins for ukukhongozela amanzi, which we used for gardening and cleaning.”

The term “grey water”, which was not in common use before the drought, became part of everyday conversations.

Messages did not reach all

More than 80% of respondents were aware of the water restrictions that the municipality imposed, but in some lower-income areas, many people indicated no awareness, notably Langa (18.8%), Clanwilliam (10.5%) and Piketberg (9.5%). This may indicate that the communication strategy and engagement across the Western Cape was less effective among specific categories of residents. In Langa, 32.4% of respondents did not think that authorities communicated well about water restrictions. Many residents in informal settlements do not receive utility bills, which may have impacted on their general awareness on water restrictions and tariff changes.

Going forward

In its policy brief, the HSRC recommends that official communication about a disaster should be timeous, clear and transparent.

Almost 43% of the survey respondents believed that the authorities handled the crisis effectively, but a third thought they had not. In an open-ended question, respondents were asked in what ways a drought could be managed in future. Almost 19% suggested enhancing communication and awareness. The most preferred communication method was television, followed by radio and posters, with people under the age of 30 years more likely to prefer online and social media platforms.

Other suggestions included the need for more stringent water saving (22%); better maintenance of existing water-storage infrastructure and the establishment of new water-storage capacity (18%); and subsidisation of the installation of storage tanks (7%) and boreholes (6%).

Given that there was a general willingness to cooperate, the HSRC recommends that water restrictions should be strict and imposed for longer periods when necessary. Messaging should continue during wetter periods to sustain the new water-saving culture and be tailored to different target groups. There is a need to refine legislative guidelines to improve and promote water usage and management behaviour, including better building codes and municipal standards for grey-water systems and run-off re-capture. Other suggestions from respondents included non-punitive water management devices, positive behaviour feedback systems such as credit rewards on their water bills, and the installation of community water-storage tanks.

Contact: srule@hsrc.ac.za