The lingering impact of COVID-19 on persons with disabilities

The diverse needs of persons with disabilities need to feature in pandemic interventions, and also in the disaster-mitigation planning for the recovery phase. Photo: Freepik

The worst socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 fell along geographic, racial, and gendered lines. A new study conducted by the HSRC, the Institute for Development Studies in the UK, and the National Council of and for Persons with Disabilities, shows that people with disabilities were also disproportionately affected, and that the government’s response did not adequately provide for this sector of the population or its diversity. This is particularly concerning given that as many as one in five people in South Africa over the age of five have some form of disability. By Andrea Teagle and Antoinette Oosthuizen

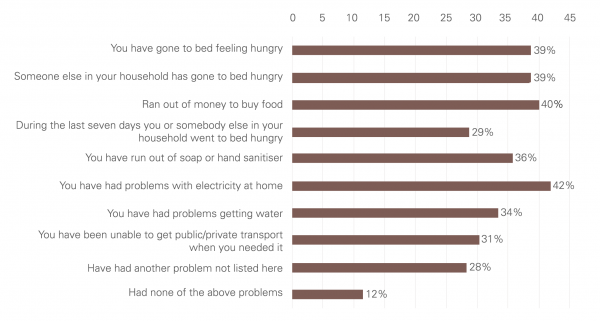

In a recent (July–August 2021) survey of the experiences of people with disabilities during COVID-19, 13% of participants (35% of those employed) reported having lost their jobs because of the pandemic. Although the survey relied on voluntary participation and was therefore not a random sample, the results do suggest that people with disabilities were more likely to be made redundant than other workers. The survey also revealed that 3 in 4 respondents (76%) had difficulty paying for their living expenses due to their financial situation because of the lockdown. And one in four (29%) indicated that they or a member of their household had gone to bed hungry in the week before answering the survey – more than a year after the first hard lockdown. See Figure 1.

Figure 1: Experience of events during the pandemic that were not normally experienced.

According to the HSRC’s Dr Tim Hart, the measures implemented during lockdown were not disability inclusive and did not consider the diversity of persons with disabilities. Where government assistance was offered – for example a temporary increase in the disability grant, food parcel delivery at community centres, or sign language accompanying televised COVID-19 messaging – information did not always reach the intended beneficiaries. Food parcels were often unobtainable by those who had some degree of immobility and could not get to the collection points. About half of the survey participants were not aware of any focused government effort to support persons with disabilities. The third who were aware of such efforts mainly noted the temporary increase in the grants and the emergency social relief of distress grant.

Six out of 10 participants said they had some difficulty with accessing information about the pandemic. In many cases, this was related to not being able to read print material or hear radio broadcasts, but it was also due to television broadcasts not having captions and the sign language interpreters not being visible enough.

About half of participants indicated that they believed the general government (51%), the government’s social and health sectors (49%) and non-governmental institutions (48%) did a ‘bad job’ in accommodating the needs and rights of persons with disabilities in their responses to the pandemic.

Financial struggles

The study, supported by the UK Research and Innovation’s Newton Fund, specifically aimed to reach persons with disabilities and not the organisations that represent them. Participants could be aided by family, friends, parents, guardians and carers, but the purpose was to hear their voices. The majority of the 1 857 participants were black South Africans (83%), and disabilities included challenges with vision, hearing, mobility, communication, self-care, concentration and memory. Respondents also reported upper-body immobility, lack of use of hands, and experiences of anxiety or fear, stress and depression (psychosocial challenges).

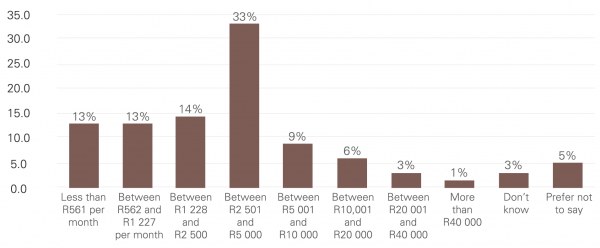

Although 79% received a social grant from the government, just 31% received a disability grant and 33% received the temporary COVID-19 social relief of distress grant of R350 per month. The remainder received old-age pensions (10%) and child support, care or foster grants (5%). One in five (21%) had been denied a disability grant by the state because of the income means test (19%) or because the state did not recognise their disability (2%). See Figure 2.

Some participants relied on state facilities (37%) to access disability-related services, 25% on organisations such as NGOs and 20% on family and friends. Many had these services disrupted during the pandemic. Over half (51%) said they were currently reliant on support from disability service organisations. With 60% relying on the services of a caregiver or support for daily activities, many experienced disruptions of this care during lockdown. In most cases, the services were unavailable for only a day (29%), but in some cases for weeks and months or it was still ongoing.

Figure 2: Monthly income of persons with disabilities during the pandemic (N=1 857)

Before the pandemic, most participants were already struggling financially: 13% lived on an income below R561 per month and 13% on R562 to R1 227. Another 14% lived on R1 228 to R2 500, and 33% on R2 501 to R5 000. Half (49%) the participants struggled to cover their disability-related expenses.

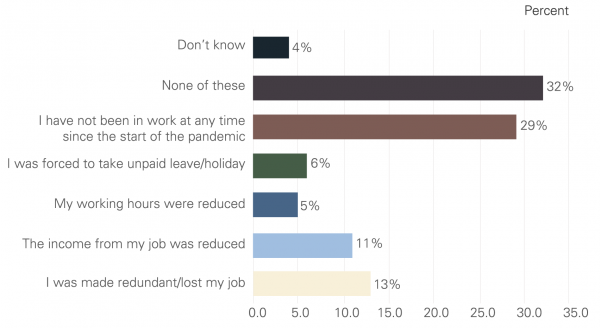

Only 37% of the participants reported being in full-time, part-time, casual or self- employment during the pandemic, while 35% were unemployed. The remainder were unable to work, doing unpaid care work, or were students or pensioners when lockdown started. A follow-up question revealed that one in three (35%) experienced some change in employment conditions at some point during the pandemic: 13% lost their jobs and the remainder had income or working hours reduced or were forced to take unpaid leave. See Figure 3.

Figure 3: Changes in employment status (N = 1 857)

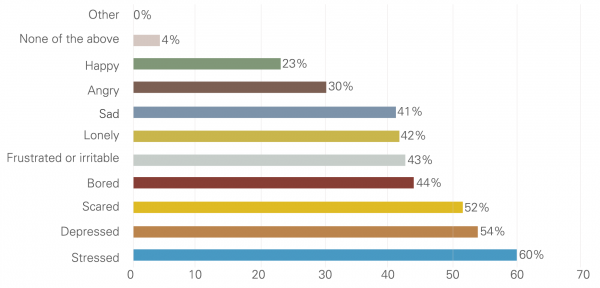

About half of the participants expected their financial situation to worsen in the following months because of the pandemic’s economic consequences. Six in 10 participants reported feeling stressed, and half reported experiencing depression (54%) and fear (52%). See Figure 4.

Figure 4: Psychosocial perceptions of the pandemic and lockdown

Prioritising people with disabilities

Although 8 in 10 (78%) of participants indicated wanting to get the COVID-19 vaccine at the time of the survey (July–August 2021), only 5% had been vaccinated. Persons with disabilities were not regarded as a priority group for the vaccine programme, despite some of them being particularly vulnerable to respiratory illness due to their disabilities.

According to Hart, the diverse needs of persons with disabilities need to feature in pandemic interventions, and also in the disaster mitigation planning for the recovery phase. Many people with disabilities also face other challenges, such as living far from places of work in informal settlements or townships, facing gendered wage gaps or contending with low educational or job opportunities.

“The results of the study provide clear evidence that it is crucial for government to take an intersectional approach in mitigating the impact of disasters and to be aware of the impacts of their mitigation regulation on vulnerable members of society,” Hart said. “The evidence indicates that mitigation measures were about controlling the spread of the virus, and no thought was given as to whether these regulations would benefit or have unintended negative impacts on persons with disabilities.

“We must remember that this is a diverse group, and an intervention is not going to accommodate all persons with disabilities equally or at all.”

Listen to the following interviews conducted with HSRC researchers: Tim Hart on NewzRoom Afrika, 14 October, at 7:30 am. The interview is available here. Gary Pienaar was on SAFM The Talking Point at 10:40 am. His interview is accessible here. An in-depth analysis of the survey data will be released in the following months.

Researcher: Tim Hart is a senior research manager in the HSRC’s Developmental, Capable and Ethical State research division. He is profoundly hearing impaired.