Using multi-voiced and creative approaches to enhance COVID-19 messaging: Learning from East and Southern Africa

While effective public communication is key to curbing the spread of COVID-19, there is no one-size-fits-all plan for all countries. Konosoang Sobane, Susan Nyaga, Medadi Ssentanda and Malwande Ntlangula explore how language diversity and multimodality have been harnessed to drive COVID-19 messaging in Kenya, Uganda, South Africa and Lesotho, with a focus on multilingual communication.

The emergence of COVID-19 highlighted the value of effective communication during a crisis, especially in the context of a virus that is not fully understood but affects almost all aspects of people’s lives. Access to clear and reliable communication helps people to make informed decisions and change their behaviour to prevent getting infected or spreading the virus.

A clear understanding of messages may, however, be threatened by the amount of overwhelmingly sensationalist content spread via several online channels, creating what researchers have called “digital pandemics” or “misinfodemics”.

In multilingual Africa, the language barrier is an additional factor which may compromise the reach and impact of communication efforts - most of which are in European languages and accessible to a fraction of the population. In many African countries, access to information is also often affected by socioeconomic and structural barriers, creating a need for reflection on how to diversify communication platforms to enhance the reach of messaging.

The researchers were interested in the East and Southern African regions because of their language diversity. In East Africa, 68 languages are spoken in Kenya and 42 in Uganda – yet they have the same official languages, English and Kiswahili. In Southern Africa, in Lesotho and South Africa English is mostly used as the official language, while both countries have Sesotho as another official language. The researchers looked at COVID-19 communication practices in the public domain, sourced from online portals, and social and mainstream media.

Multiple voices and public agency as enablers of information access

In all four countries, multiple and diverse voices conveyed COVID-19 messages to the public, each with a specific appeal and potential influence on a particular section of the population. Communication through multiple voices enables contextualisation and simplification of information, making it more accessible to the public.

The multiple voices include the authoritative voice of the government, complemented by those of the media, creatives and civil society, who repurpose and repackage messaging in different formats to enhance its reach and consumption.

In official messaging there is a tendency towards heavy reliance on English, despite the well-known multilingualism of African communities and low levels of competency in English. For example, in Uganda the presidential public addresses on COVID-19 have largely been in English, with occasional translation of words or phrases into Luganda (the dominant local language) and Runyankore (the president’s mother tongue). When local languages are not used, population groups that have insufficient proficiency in the language are restricted from accessing the information. Complementing voices that repurpose, repackage and translate these messages are valuable tools to address the communication needs of groups such as the above.

Multimodality in enhancing the reach of messaging

Multimodality refers to the use of a variety of communication methods, including writing, audio-visual products and the creative arts to convey messages. These modes offer innovative ways to capture and retain the attention of different audiences, minimising the risk of them disengaging when confronted with frightening information about a potentially life-threatening disease.

They are often constructed in local languages, making the messages accessible to the majority of the population who are local language speakers. Audio-visual communication in the form of videos and creative arts such as poetry, music and comedy were found to be common in COVID-19 communication in the four countries.

Creative arts: Music and comedy

A variety of music productions by local artists conveyed messages on COVID-19 prevention. The productions harnessed language diversity by using local languages and traditional dance, often combined with visual illustrations, as modes of expression. By contextualising them, the messages resonated with local-language speakers. This increased the potential buy-in of the audiences, because of their familiarity with the language and the relatability of the actions and, in some cases, the actors.

Most of these productions had translated sub-titles, an inclusive approach catering for the communication needs of people with diverse literacies. They were mostly published as video-clips on social media, capitalising on the wide reach of such platforms. For example, the Ndlovu Choir, a traditional music group from Limpopo, released a song in isiZulu explaining some of the basic guidelines to combatting COVID-19. In another context, Mosotho hip-hop artist Ntate Stunna produced a song with the same aim. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Music productions about COVID-19 in Lesotho and South Africa

Beyond multilingualism, the body language in the videos is intensely expressive and complements the lyrics. Also, the artists are role models among the youth and their popularity adds to the appeal of the messages to this audience.

Comedy was another prevalent form of messaging, appealing to the humour of the target audience. A series of short comedy videos on the Facebook page of Lilaphalapha, a stand-up comedian in Lesotho, explores fictional storylines on the effects of the coronavirus and its prevention. The characters, their physical appearance and the physical location portray a rural context, which many Basotho could relate to, since it was part of their upbringing. (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Screengrab of a video by Lilaphalapha, courtesy of Lilaphalapha media productions in Lesotho

Being able to relate to a message enhances its potential uptake. The comedians combined many expressive modes of conveying messages, including facial expressions and body language, body movements, gesturing and blending of languages to disseminate messages in a humorous yet educational way.

Posters

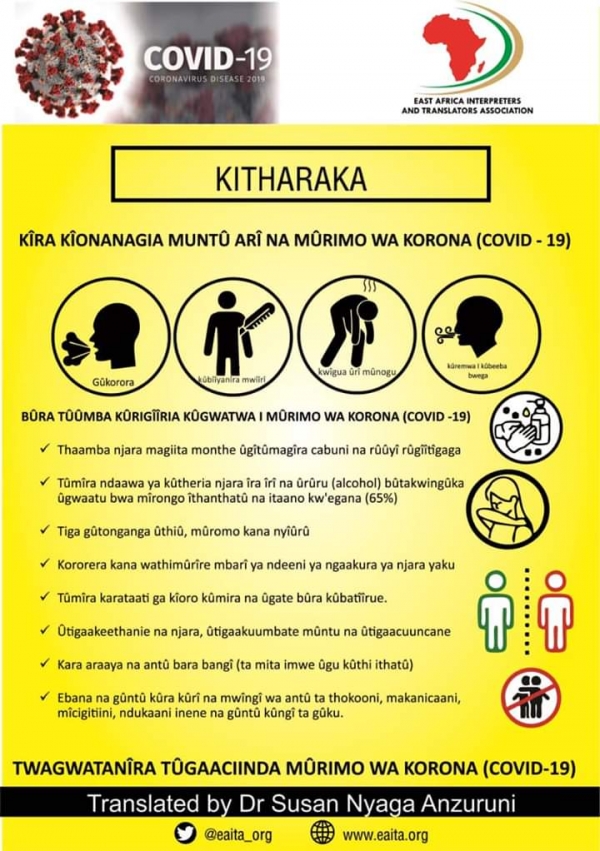

In some cases, multilingual communication was by using posters with visual illustrations of key COVID-19 messages translated into local languages. For example, in Kenya a private organisation facilitated translation of COVID-19 messages into 20 Kenyan languages, including Kitharaka, and presented them in poster format. These posters also had illustrations to make the messages accessible to those who are not literate. (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Poster design and translation facilitated by the East Africa Interpreters and Translators Association

In Kenya, an artist used graffiti in slum areas to urge people to wash their hands and wear masks. While there are few or no words in these pieces, which are found in places like Mathare, the Kenyan capital’s second-largest slum, they have become an influential means of conveying COVID-19 messages. (Figure 4)

Figure 4: Graffiti messages on COVID-19 in Kenya

These pieces of art offer practical guidelines on avoiding infection in residential areas that are congested, and where practices like physical distancing are almost impossible.

These multilingual, multimodal practices offer an opportunity to enhance the reach and possibly the uptake of messages, which are communicated; however, they are fragmented and have not been integrated. It is therefore recommended that those involved in disseminating messaging make deliberate efforts to diversify communication, with considerable reflection on the communication profile of the targeted audiences.

Authors: Dr Konosoang Sobane, a senior research specialist, and Malwande Ntlangula, a researcher in the HSRC’s Impact Centre, Dr Susan Nyaga, a senior literacy and education consultant at SIL International, and Dr Medadi Ssentanda, a lecturer in the Department of African Languages at Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda

ksobane@hsrc.ac.za