Remember our mental health during the lockdown: The voices behind the numbers

A recent survey by the University of Johannesburg and the HSRC found that a sizeable share of South African adults experienced a range of negative emotions during lockdown. The chief driver was hunger resulting from poverty. The depth of psychological distress and social isolation was highlighted by survey participants’ moving responses when asked to share “the worst thing” about lockdown. By Mark Orkin, Ben Roberts, Narnia Bohler-Muller and Kate Alexander.

More than a hundred countries spanning nearly half the planet’s population have implemented full or partial lockdowns in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, in what has been described as “the largest psychological experiment in the world”. In April 2020 public-health experts warned in an academic article that “it appears likely that there will be substantial increases in anxiety and depression, substance use, loneliness, and domestic violence”.

In South Africa, among the most unequal societies in the world, the circumstances of people during confinement differ dramatically: from a minority of comparatively well-off families or individuals in suburban houses or apartments, to mainly less well-off families in townships, informal settlements and rural areas. The poorest depend on child-support grants, grandparents’ old-age pensions and remittances. For such families with scant savings, and with their wage-earners often dependent on casual or informal-sector employment, the economic effect of confinement has been devastating.

However, the way in which these factors have an impact on our population’s mental health has received little empirical attention. Research by an HSRC-led public-health consortium has indicated that South Africa is in a “moment of psychological crisis”. Using evidence to profile the mental health of South Africans under lockdown is critical for a holistic response to COVID-19.

Online survey

The first wave of surveying was conducted between 13 April and 11 May using the Moya Messenger App on the #datafree biNu platform. The survey employed opt-in cell-phone sampling, but the 12,312 complete responses were weighted to StatsSA demographics, meaning the results are indicative of the national situation.

During the survey, respondents were asked the following: “Now we want to ask you a question about the effect of the lockdown on you emotionally. Which of the following emotions have you felt often during the past week?” A list of eight different emotions followed, to which they answered yes or no. In addition, an open-ended question asked about their “worst experience” under lockdown.

Exposing the hidden mental struggle

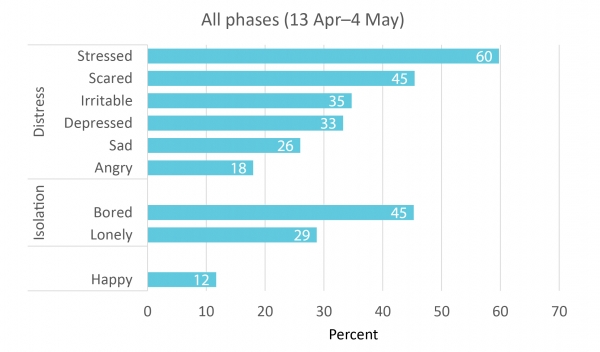

During lockdown, 60% of South Africans were frequently stressed and 45% scared and bored (Figure 1). Around a third were depressed (33%), irritable (35%) or lonely (29%). Sadness was experienced by 26% and anger by 18%. In contrast, barely a tenth reported feeling happy (12%). Depression has been clinically measured at between 18% and 27% in less unusual times, so it is likely that there was an appreciable increase.

Women are more depressed than men (36% vs 31%) and more apprehensive (50% vs 42%) – perhaps because they bear the brunt of extra child-care. Possibly for the same reason, they report being somewhat less lonely (27% vs 30%).

Differences by age are more striking. Among 18–24-year-olds, 59% felt bored compared to only 29% of those aged 65+ years. The pattern was similar for anger, at lower levels: 22% among 18–24-year-olds vs 12% among those aged 65+ years. Fear, stress and depression also taper off after the mid-40s. The young clearly experience the psychological effects of lockdown more severely.

Figure 1: The pattern of emotional experiences under lockdown, 13 April - 11 May (% experiencing each emotion frequently during the week prior to the interview)

A selection of intense responses provided by survey respondents in sharing "the worst thing" about lockdown

Scared:

“There is no limit to the people [who] come into the store. So it puts me and my colleagues at high risk.”

“Spending without getting any sort of income really scares me.”

“People are not ready to listen. I’m afraid if one person in my community is affected then [we] will have thousands of people sick. We are using one pipe of water and the community is about 800 shacks. May God help us.”

“Having a fear of getting the virus, [because] I work at a supermarket and [bring risk to] my baby and family.”

Stressed:

“Knowing that my parents are stressed about where we are going to get our next meal if the president decides to extend the lockdown.”

“We are a big family of seven in an informal settlement. My mother is a breadwinner ... I can feel the pain of seeing her going through tough times.”

“I am stressed ... my boss told me that she will be able to pay me for three weeks as it was a small business ... after that she won’t be able to.”

“Not knowing how will I get money to pay rent. That issue is stressing me a lot, how will I eat?”

Depressed:

“Production has stopped altogether. At times I feel depressed, like life is not worth living anymore.”

“High stress, anxiety and depression. No alcohol to relieve this ... I am a pensioner living on my own, so no-one to share my problems with. Taking too many tranquilisers to cope.”

“It’s depressing! Can’t go out, struggling to continue with my job searching.”

“I just wish you had organised with varsities to let students stay in residence because now many of us will not have access to the internet for online learning, we are being abused at home and are now suicidal. It sucks seeing myself in this dark mental space.”

Sad:

“Watching my kids get sad and angry at the restrictions and I cannot take them outside”

“Most people in my community don’t work and don’t have food – very sad.”

“The worst thing for me is that I’m a graduate who was due for employment as of the 1st of April, I was also supposed to attend my graduation ceremony ... I’m really sad because none of that happened.”

Irritable:

“Getting frustrated with my household and enormous pressure due to school children missing a lot of work.”

“No money, can’t get my smokes, which makes us more irritated. Withdrawal is bad”

“The worst thing of lockdown is you can’t go anywhere and it’s frustrating.”

“We are not able to go to school … it affects our minds, sitting and doing nothing at home is frustrating, learning is the key.”

Angry:

“Being locked up when I feel like going somewhere I want — it makes me angry so much.”

“Not able to work and no money; being stuck with my angry father.”

“It’s very stressful during this lockdown to live in the same yard with so many harsh words and anger.”

“People aren’t taking the virus seriously that makes me very angry cause they can infect other people.”

Boredom:

“Not being able to go to school or not seeing my friends. Also, it gets boring cause we don’t have WiFi or data.”

“I can’t see my loved ones and it’s boring at home”

“It’s boring in the house [because] we are not able to do the things that we love.”

Loneliness:

“I cannot really help my elderly mom and she is very lonely.”

“Being alone and not being able to comfort a friend in their time of need”

“Not being with my family ... I’m all alone in my flat”

“No hugs from my family and friends. I live alone so I really miss that.”

“Feeling lonely, unable to share useful information with others like before and less productive when it comes to my studies.”

Drivers of psychological stress and isolation

Statistical analysis divided these eight negative emotions into two underlying psychological factors, as indicated by the graph: psychological distress, which includes being scared, stressed, depressed, sad, irritable or angry; and social isolation, which includes feelings of boredom and loneliness. Further analysis showed that the strongest predictor of distress was hunger, experienced by nearly a third (31%) of participants. Compared to those who did not experience hunger, being hungry resulted in an increase of sadness by 9 percentage points. Anger increased by 12, stress by 15, depression by 17 and loneliness by 5 percentage points.

Predictably, absence of hunger correlated strongly with income, and income with having employment. This signals the importance for mental wellbeing of continuing the phased reintroduction of access to work and wages, as fast as can safely be achieved.

In response to the “worst thing” write-in option, the most frequent response was not having enough food to eat, especially because of unemployment:

“Food gets finished quickly while everyone is at home ... Nobody is working, we try and live by what we have.”

“I am an unemployed mother of three kids and I don’t know where my next meal is coming from”

“My family is hungry, UIF takes 35 days to apply for. What must my kids eat?!”

“We haven’t received any food parcel; we didn’t even get forms to fill in for food parcels. Our council is useless, so tell me Mr President how can you let most of us go hungry? We are only good for votes.”

“Hunger. Hunger. Hunger. The worst thing I’m worried about is food more than the coronavirus itself.”

Prioritising mental wellbeing

These data-driven observations are potentially powerful and may assist authorities in their decision making. This scary, unavoidable worldwide ‘experiment’ will end. Yet, as both our president and the South African Depression and Anxiety Group have warned, it requires concerted attention and the correct measures. Addressing mental distress and isolation, no less than their prime socioeconomic determinants, must be part of the mix. The words of the public offer a haunting reminder of how critical this priority is:

“Please remember that there is both physical health and mental health. Too much stress is just as dangerous as the virus.”

“Please make means for psychological help or therapeutic help ...”

Authors: Dr Ben Roberts is a chief research specialist and Prof Narnia Bohler-Muller the divisional executive in the HSRC’s Developmental, Capable and Ethical State research division. Dr Mark Orkin is an associate research fellow and Prof Kate Alexander the director of the Centre for Social Change at the University of Johannesburg.

Note: A more quantitatively focused earlier article was published in the Daily Maverick and a webinar discussion on the findings can be accessed here.

The second wave of the online COVID-19 Democracy Survey is being conducted on the biNu Moya Messenger App between 6 July and mid-August.

This can be undertaken, free of charge, by anybody in South Africa aged 18 years or over with access to the internet. Go to: https://hsrc.datafree.co/r/ujhsrc