HSRC-UJ survey findings call for state and civil society collaboration to rebuild trust

Children wait for food in Lavender Hill during the COVID-19 lockdown in Cape Town.

Photo: Brenton Geach

A recent HSRC-University of Johannesburg COVID-19 survey revealed that South Africans are willing to make sacrifices to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus. However, these cooperative responses are partly contingent on trust in the government, the police and the army. At a recent webinar highlighting the findings, the survey team spoke about the need for the government to partner with civil society and to prevent starvation in the face of the pandemic. By Andrea Teagle

Approximately two-thirds of South Africans said they would be willing to sacrifice some human rights to prevent the spread of COVID-19; and over three-quarters of adults across socioeconomic groups agreed that food parcels should be given to those who need them.

These are some of the findings of the COVID-19 Democracy Survey undertaken by the HSRC and the University of Johannesburg, that point to feelings of social solidarity and cooperation among South Africans during lockdown.

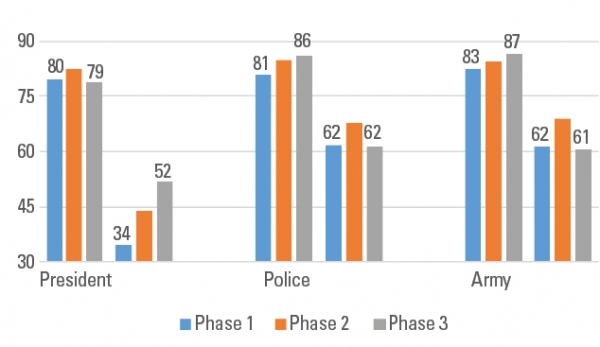

The survey also found that willingness to sacrifice some human rights was predicted by trust in the government, army and police. (Figure 1) For example, in phase one of the study, just 34% of people who distrusted President Cyril Ramaphosa were prepared to sacrifice rights, compared to 80% of those who trusted him.

However, trust in the government has declined amid reports of corruption in the expenditure of social relief grants, heavy-handed enforcement and the perceived irrationality of some of the lockdown regulations. This pushback was reflected in the recent North Gauteng High Court ruling, due to be appealed by the government, that lockdown level 3 and 4 regulations are invalid.

Figure 1: Willingness to sacrifice some rights by trust in the president, police and army (%)

One survey participant, a woman in the 45–54-year age range from Kenilworth in the Western Cape, implored Ramaphosa to trust citizens to do the right thing:

“Stop your ministers from treating us like children who need to be micromanaged and punished for inadvertently breaking a rule. If the police and army can’t be kind in the face of the pandemic, then take them out of the townships.”

Reports of socioeconomic and psychological distress increased during lockdown, with communities stepping up to try to fill the gaps left by the government’s social grant scheme. “Thanks for everything, but please we are hungry,” said another participant, a woman (25–34 years) from Cacadu settlement (formerly Lady Frere) in the Eastern Cape.

Speaking at a webinar presenting the findings of the study, co-principal investigator Prof Narnia Bohler-Muller from the HSRC emphasised the need for the government to work with communities to retain public trust: “If trust is to be maintained, the establishment of platforms for collective action and citizen participation are necessary.”

Divergent lockdown experiences

At the webinar, HSRC CEO Crain Soudien called for collaboration between biologists and social scientists in informing the government’s response to the pandemic. “It’s important in coming to understand how illnesses are always socially determined,” he said.

The survey attempted to add to the mostly clinical research informing government policy by capturing the psychosocial and economic experiences of lockdown, before the move from level 5. Led by Bohler-Muller and UJ’s Prof Kate Alexander, the HSRC-UJ survey team faced the challenge of reaching a representative sample of the population given limited time and mobility.

In place of telephone interviews, the team made use of the Moya messaging app on the data-free biNu platform, which enabled access to all people over 18 who owned a mobile phone. The survey was conducted in three phases: phase one, 13–18 April, phase two, 18–27 April and phase three, 27 April–13 May 2020.

Speaking at the seminar, Prof Mark Orkin from UJ said that the data-free platform had been critical to success. The resulting diverse database, comprising 12,312 responses, required only slight weighting — by race, age and education - to be nationally representative.

Alexander noted that despite the convergence in opinions on matters related to social relief - such as widespread support for the provision of food parcels — experiences of lockdown were widely divergent across socioeconomic and racial groups. (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Findings on hunger and food parcels

Hunger loomed large over low-income individuals (monthly household income < R10k), who comprised the vast majority (83%) of respondents. A third (34%) of lower-income households reported going to bed hungry during lockdown.

“There was a large gulf between [lower-income] adults and those on high incomes,” Alexander noted, with only 3% of higher-income individuals reporting having gone to bed hungry. Hunger was the strongest driver of composite psychological distress, which includes feeling scared, depressed, sad and irritable, said the HSRC’s Dr Ben Roberts.

Low-income households were also significantly more worried about the impact of lockdown on their children’s education, with 82% expressing concern compared to 32% of higher-income parents. This points to the longer-term impacts of the pandemic again falling along socioeconomic and racial lines.

Community cooperation

Referring to the shared willingness to sacrifice rights to slow the spread of the virus, Bohler-Muller said, “We can see there’s quite a lot of empathy and altruism involved here, but also, in a sense, self-interest because if we protect others, we’re also protecting ourselves.”

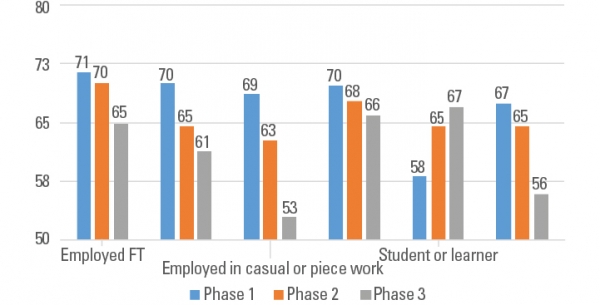

However, over the three phases of the survey willingness decreased from 68% to 62%. The drop was particularly pronounced among individuals employed in casual or part-time work. (Figure 3) In addition, willingness was not met with adequate support from the government to translate into optimal health-promoting behaviour, particularly among low-income households. The survey indicated that 44%, 55% and 57% of lower-, middle- and upper-income individuals respectively reported wearing masks. The corresponding figures for social distancing were 69%, 88% and 93%.

Figure 3: Willingness to sacrifice some human rights by employment type (%)

“Despite material problems with physical distancing in densely populated areas and with wearing masks ... most poorer people do protect themselves with these measures. And more could do so, if the state and civil society co-operated with provision of public education and free masks,” Alexander observed.

Bohler-Muller emphasised that a state of national disaster, unlike a state of emergency, does not affect the supremacy of the Constitution or the Bill of Rights: “[Socioeconomic rights] cannot be limited. Obviously, the most important one that we are considering now to save lives is access to health care, but food, water, shelter and social security are rights that must continue to be fulfilled.

“Amongst activists, there is an increasing recognition of the failure of the government to assist in many areas, and some of them are raising the idea of Asivakelane — ‘Let us protect each other’,” Alexander said. This sentiment is reflected in the sprouting of community-led aid programmes around Cape Town, such as the Community Action Networks.

Alexander highlighted the responsibility of the government and civil society to respond to the widespread hunger: “If we’re to avoid people starving to death, then it’s critical that free food is provided for a large proportion of the vulnerable population of South Africa … it’s something that we need to address as a society.”

Author: Andrea Teagle, a science writer in the HSRC’s Impact Centre

ateagle@hsrc.ac.za

Researchers: Prof Crain Soudien (HSRC CEO), Prof Mark Orkin (Associate Research Fellow at UJ’s Centre for Social Change), Prof Narnia Bohler-Muller (HSRC Divisional Director), Prof Kate Alexander (Chair of Social Change at UJ), Dr Benjamin Roberts (HSRC Research Director), Dr Yul Derek Davids (HSRC Research Director), Prof Carin Runciman (UJ’s Centre for Social Change).