Who might engage in anti-immigrant violence

On 17 October 2018, Leonard Hlathi, police spokesperson for Mpumalanga Province, urged foreign nationals in the town of Middelburg to move to safer places following anti-immigrant violence and vandalism in the area. The continuing incidents of anti- immigration aggression happen so often in South Africa that they no longer attract much attention from the media. Dr Steven Gordon shares the latest research results of the HSRC’s ongoing Immigrant Related Attitudes and Behaviour (IRAB) project that looks at the drivers of this kind of violence.

People marching against xenophobia outside Little Ethiopia in Jeppe street, Johannesburg. Despite such events being well attended, an HSRC survey showed that a significant percentage of people who had never taken part in violent action against foreign nationals, were prepared to do so. - Dyltong, Wikimedia Commons

Over the last few decades, sporadic eruptions of xenophobic violence in South Africa have claimed lives, destroyed businesses and displaced immigrants in several parts of the country. For years, researchers have been trying to identify and understand the drivers of this phenomenon. In 2008 a previous HSRC study identified intense competition for jobs, commodities and housing, as well as South Africans’ feelings of superiority in relation to other Africans, as contributors to violent riots across the country. The International Organisation for Migration blamed township politics for those attacks and found that poor service delivery or an influx of foreigners may have contributed.

To contribute to the growing body of research on xenophobic behaviour, researchers from the HSRC’s IRAB project used public-opinion data from nationally representative surveys to try and understand who participates in anti-immigrant aggression in South Africa. The project looks at a range of different behaviours such as boycotts and demonstrations targeted at immigrants.

Participation in xenophobic behaviour

In one study, the IRAB project’s researchers used data from the 2017 South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS). SASAS is an annually repeated, cross-sectional opinion survey of adults of 16 years and older living in private households. The sample size for the 2017 survey was 3,098. In the SASAS questionnaire, respondents were told they would be asked a few questions on people from other countries coming to live in South Africa. Respondents were then asked if they had taken part in the following acts to prevent immigrants from living or working in their neighbourhood:

i. “asked foreigners to leave your neighbourhood” (verbal action)

ii. “boycotted or refused to buy things from shops owned by foreigners” (boycotting)

iii. “took part in a demonstration against foreigners” (demonstration)

iv.“took part in violent action against foreigners” (violence).

Respondents may have been disinclined to disclose this type of potentially incriminating information during face-to-face interviews on this specific subject. Another consideration is that, while researchers have been able to undertake similar research with residents from South African townships without problems, this could have led to possible underreporting of anti-immigrant behaviour when reviewing the results of the survey.

One in 20 admitted participation

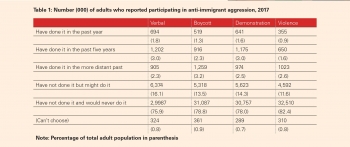

Only a minority of the South African adult population reported that they had participated in any form of anti-immigrant aggression (Table 1).

Interestingly, most of those who had participated in xenophobic behaviour told fieldworkers they had done so in the last five years. Of the four different forms of aggression under discussion, the most common types were verbal actions and taking part in demonstrations. While 5% of respondents admitted to having engaged in these activities between 2012 and 2017, only 2.5% admitted to taking part in violent xenophobic action during the same period.

A propensity for violence

One of the most troubling findings that emerged from this study concerned potential participation amongst non-participants of anti- immigrant aggression. More than 10% of respondents told fieldworkers that they had not taken part in violent action against foreign nationals but would be prepared to do so. This figure is disturbing given that people may be underreporting their propensity for violent behaviour.

The IRAB project study looked at how different anti-immigrant activities were interrelated. It found that if individuals have participated in a non-violent type of anti-immigrant behaviour, they are more likely to have taken part in more violent antagonistic types. This helps us understand how peaceful anti-immigrant activities such as demonstrations can escalate to violent riots. Therefore, policymakers must not ignore non-violent forms of anti-immigrant activity.

Conclusion

The national government has committed itself to addressing the issue of anti-immigrant violence, but policymakers should not underestimate the problem. The results of the IRAB project study show that millions of ordinary South Africans are prepared to engage in anti-immigrant behaviour. It is vital therefore that the resources dedicated to combating xenophobia be equal to the size of the problem. The IRAB project is looking to partner with national and provincial policymakers to help address xenophobic behaviour in the country.

Author: Dr Steven Gordon, senior researcher in the HSRC’s Democracy, Governance and Service Delivery research programme

sgordon@hsrc.ac.za

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by the Centre of Excellence in Human Development at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, under Grant P2018003. Opinions expressed and conclusions arrived at, are those of the author and are not to be attributed to the Centre.

Table 1