The social costs of violent and destructive service-delivery protests in South Africa

South Africa has experienced a rapid increase in violent and destructive service-delivery protests. Poor and marginalised communities are increasingly disgruntled, due to the lack of access to services, growing corruption, and the unresponsiveness of the government to the needs of communities. Looking at two case studies, Isaac Khambule, Amarone Nomdo and Babalwa Siswana considered the potential social cost of protests, where essential public infrastructure is destroyed.

The South African government recently celebrated 24 years of its democratic dispensation. While the celebrations signify great strides in the realisation of democratic values, the majority of the country’s citizens are still living in poverty (55%) with 27% unemployed (Statistics South Africa, 2017). In 2015, the Presidency revealed that approximately 80% of municipalities had failed to perform their mandatory duties, including the delivery of basic services. Service-delivery protests have been rife from 2008, but particularly violent and destructive towards public infrastructure since 2013.

This is indicative of the country’s failure to create inclusive economic development and its inability to deliver basic services to its constituents. This article argues that service- delivery protests, during which protesters destroy public infrastructure essential to development, might undermine the future capabilities of people in those communities.

Destroying what we need

There is a growing body of evidence that links the positive effect of access to service delivery to better socio-economic conditions and opportunities. Researchers describe capabilities as an individual’s and a community’s capacity to cope or recover from setbacks and to function in challenging times. People develop skills and knowledge through access to public services and education infrastructure that help them to transition out of poverty, and to social security that protects them against vulnerabilities. For example, the education that they receive at schools and libraries gives them access to job opportunities, and the counselling they receive at clinics might help them to seek medical assistance timeously. Violent and destructive protests such as the burning and destruction of public infrastructure can therefore diminish their future capabilities. Yet, people burn or destroy public infrastructure when they feel excluded or have inadequate access to services.

Burning factories in Mandeni in 2016

Mandeni is traditionally known as a manufacturing hub on the North Coast of KwaZulu-Natal. The town was rocked by protests related to the election of a ward councillor and the inability of local authorities to heed the community’s demands. The protests turned violent and led to the burning down of factories in the region, leaving more than 2 000 people out of work. As a result of the destructive protest, local residents lost sources of income and capital needed to send their children to school, access services and purchase food, which led to monetary deprivation.

Without income, access to services that are essential to improving capabilities are undermined. Results from the 2011 Youth Risk Behaviour Survey revealed that KwaZulu-Natal had the highest rate of learners with unemployed parents. In addition, it had a high rate of students who did not get pocket money, which is a good indicator of household financial capacity. The violent protests would access to education and their ability to cope at school.

The case of Vuwani

The motive behind the torching of public schools in Vuwani in 2016 was dissatisfaction about the Municipal Demarcation Board’s demarcation of a new jurisdiction that led to Vuwani falling under the Vhembe District. It was reported that Vuwani residents had depended on the previous parent municipality for jobs, and were doubtful of employment prospects and the provision of adequate services by the new municipality.

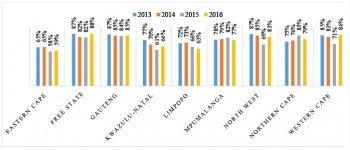

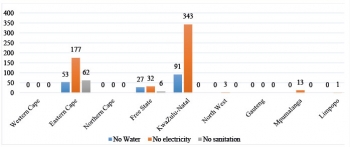

The damage to schools and the resultant shutdown affected more than 2 000 matric students, compromising their access to education and preparation for exams. To make sense of the social cost of such widespread destructive protests, we need to consider their impact on the existing infrastructure backlogs and connection between infrastructure and school performance in South Africa. There is a strong link between provinces with infrastructure backlogs and poor pass rates (KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape) and between provinces with the necessary infrastructure and high pass rates, with Gauteng and Western Cape having more than an 80% pass rate from 2013 to 2016, as evident in Figure 1 and 2.

Limpopo had a 9.3% drop in pass rate from 2013 to 2016. This indicates that the destruction of public schools in Limpopo might have had a long- term effect on the province’s pass rate, the future capabilities of school learners and the ability of schools here to attract good teachers. The destruction of existing infrastructure undermines the ability of government to improve access to public services and the social and economic opportunities of affected areas.

Breaking the vicious cycle

The destruction of public infrastructure should be viewed as burning the bridge that needs to be crossed to reach a better life. The pervasive argument forwarded in the heat of violent and destructive protests is that government values property more than the lives of ordinary people who are striking for improved service delivery and as a means to be heard. At the heart of this problem is the failure of government to engage in dialogue on the impact destroying

It is only through promoting such a dialogues that a sense of local ownership and valuing of infrastructure that communities might shy away from violent and destructive service-delivery protests. This can be achieved through better civic education, as well as through strengthened public-participation spaces at a local level – the direct line of contact for residents. Government also needs to move away from being reactive and implement proactive strategies to address these issues. Further research is needed on communities’ perception of public infrastructure.

Authors: Isaac Khambule, Amarone Nomdo and Babalwa Siswana, researchers in the HSRC’s Democracy, Governance and Service Delivery programme

Contact:

Amarone Nomdo anomdo@hsrc.ac.za

This article is based on a presentation and comprehensive draft paper currently pending publication.