The love-hate triangle between rural municipalities, traditional leaders and traditional councils and its impact on local communities

South African municipalities that include traditional communities are characterised by ‘wicked problems’, complex interdependent problems that are almost impossible to resolve. Dr Gerard Hagg and Prof. Modimowabarwa Kanyane write about the relationship between the Rustenburg Local Municipality, the Bafokeng Traditional Council and the Royal Bafokeng Nation in North West province.

Wicked problems refer to the difficulty of resolving institutional relationships between a local municipality, traditional leaders and the traditional council. Traditional structures appear to be the weakest link. What makes these relationships wicked are conflicting world views, lack of implementation of constitutional mandates, and an inability to strengthen governance institutions and hold them accountable. These issues lead to power struggles, divided loyalties, legitimacy challenges by communities and civil society organisations, lack of trust and poor service delivery. Ultimately this further entrenches poverty and inequality and stifles progressive realisation of socio-economic rights.

The governance mandate

Constitutionally and legally, the governance mandate for the Bafokeng community lies with the Rustenburg Local Municipality. The municipality is responsible for service delivery and development, with a broader provincial and national legislative framework. In line with Chapter 12 of the Constitution, the Bafokeng leadership is responsible for cultural and identity issues, and may be allocated responsibilities for certain services.

Though a ward councillor and ward committees exist, they also fall under the village leadership and are of a lower status than the village makgotla (meetings). The Bafokeng leadership interprets cultural and identity issues as including development, and, to some extent, service delivery.

The traditional council was established in terms of the Traditional Leadership and Governance Framework Act (41 of 2003), and the kgosi (chief) ensures proper ratios of male-female membership. However, the traditional council functions under significant limitations as its members are of a lower status than the dikgosana (headmen). In reality, the traditional council has been absorbed by the Bafokeng leadership.

Traditional leadership taking over

Substantive revenue generation from platinum mining has enabled the leadership of the Bafokeng traditional community, near Rustenburg Local Municipality, to take over development and service provision for Bafokeng.

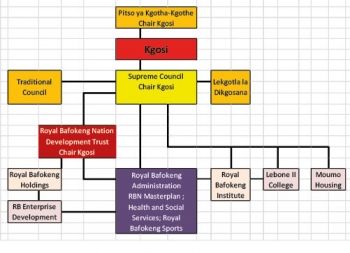

An important part of the strategy was to combine the Bafokeng identity as a traditional community with its modern future visions. To this end, the leadership established an extensive institutional structure to manage the take-over of service delivery and development and established the name Royal Bafokeng Nation. Examples of traditional institutions are the kgosi, the Lekgotla la Dikgosana (council of headmen) and the Pitso ya Kgotha-Kgothe (main community meeting). Modern business organisations that were established to manage mining relationships and revenue, were named Royal Bafokeng Holdings Company and the Royal Bafokeng Development Trust. This organisational complexity is supported by a quasi-municipal administration (Bafokeng Administration). Figure 1 shows this organisational conglomeration.

Competitive cooperation

Until 2015, this organisational structure (Figure 1) and abundant revenue allowed the Bafokeng leadership to successfully exclude the Rustenburg Local Municipality from service delivery and community development. The traditional council, which reports to the North West provincial government and the Bafokeng community, has largely lost its independence due to its functional absorption into the supreme council. Although a memorandum of understanding exists between the Royal Bafokeng Nation and Rustenburg Local Municipality, cooperation was largely competitive. As the Royal Bafokeng Nation’s land is private – in the past, the Bafokeng bought most of the farms – the municipality cannot act or deliver services without their permission.

The community’s divided loyalty

From the 2011 and 2016 Population and Use of Land Audits, it is clear that the community supports both the municipality and the Bafokeng leadership. Community attitudes are largely determined by the ability of these parties to deliver. Disappointments among the Bafokeng include the inability of the Bafokeng-funded prestige Lebone II College to serve all of Bafokeng, as well as water and sanitation supply constraints. In addition, some 22 families have established the Bafokeng Land Buyers Association, to challenge the attempt of the leadership to register title deeds for all land in the community in the name of Kgosi Molotlegi. The families’ argument was that their ancestors bought the land and were later forced by apartheid legislation to join the Bafokeng tribe.

Not delivering on promises

The power struggle has long been skewed towards the Bafokeng leadership, but it has changed significantly over the last few years as a result of a drop in platinum prices and the increased influx of non-Bafokeng mineworkers. The platinum price substantially dropped after 2009 and through a five-month strike in other platinum mines in 2012. The combination of increased overhead costs and lack of sustainable revenue, undermined the ability of the Bafokeng leadership to deliver on their promises. This led to dissatisfaction among the Bafokeng. After 2010, non-Bafokeng mineworkers moved out of hostels

Challenges

The Bafokeng leadership therefore experienced at least four challenges to its dominant position. Although a municipality can obtain additional grants from the national government, such resources are not available to traditional leaders. Lower revenues compelled the Bafokeng leaders to revisit their memorandum of understanding with the Rustenburg Local Municipality and provincial departments to sustain service delivery. This could strengthen the position of the municipality and the ward councillor, if the municipality increases its service delivery. The second challenge is the need to strengthen the role of the traditional council, as it is the only recognised governance structure among the kgosi.

This could create tensions within the supreme council and at village level, and result in a less functional traditional council. As this council is partly responsible for decisions on service delivery, its lack of real power may result in a deterioration of service delivery. The third challenge is that of the Bafokeng Land Buyers Association, which may secede from the traditional community in order to obtain its own share of the platinum revenue. Combined with contestations by non-Bafokeng villages in the area to the authority of the traditional leadership, such activities may decrease trust in the leadership in general. Lastly, the combination of customary values with modernity may ultimately be replaced by new identity formations among younger generations. Social media and communication technology tend to instil a global identity among the youth, with association and solidarity becoming based on general modern South African values.

These include the primacy of individual rights rather than customary communality and identity, and a focus on modern material wellbeing rather than customs. The combination of these challenges may ultimately undo a lot of the development initiatives of the leadership, and increase the navigation patterns of the Bafokeng between municipal and traditional institutions, to satisfy their needs.

Authors: Dr Gerard Hagg, chief research specialist, and Prof. Modimowabarwa Kanyane, research director, in the HSRC’s Democracy, Governance and Service Delivery research programme

ghagg@hsrc.ac.za bkanyane@hsrc.ac.za