Depression symptoms in South Africa

Some people suffer a disproportionate burden of depression, which affects their quality of life, economic productivity and physical wellbeing. Researchers from the HSRC and University of the Witwatersrand found a statistically significant relationship between the subjective social status and the prevalence and severity of depression symptoms reported by respondents to a South African survey. Chipo Mutyambizi reports.

How it feels sometimes. A man in the streets of Kempton Park, Gauteng Photo: Karabo Diseko, Unsplash

According to the World Health Organization, depression is one of the most common mental disorders, which affected more than 4% of the global population in 2015. It is the single largest contributor to global disability, accounting for 7.5% of years of life lived with disability. Research has also shown that depression is unequally distributed within society, being influenced by various social, political and economic factors. In South Africa, studies based on objective measures of socio- economic status have shown that depression is more concentrated among the poor, but literature also suggests that a person’s subjective social status is an equally important predictor of health.

The South African context

In South Africa, huge socio-economic inequalities, crime, violence against women, perceived racism and victimisation may place people at an increased risk of depression. These factors are important underlying determinants of a person’s subjective social status, which is why this HSRC study sought to estimate the role of subjective social status-related inequalities in the prevalence and severity of depression in the country. The researchers also examined the factors that contribute to such inequalities.

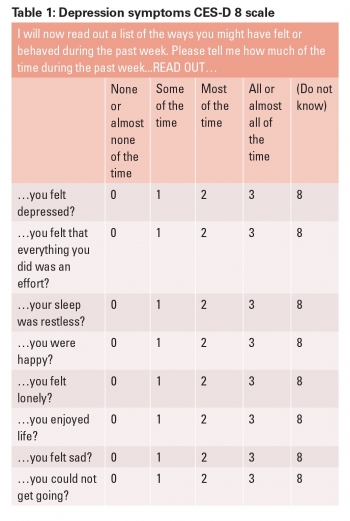

Prevalence and severity of depression symptoms

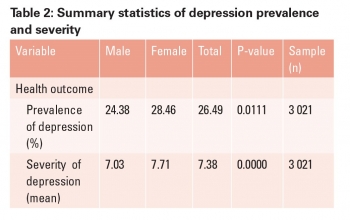

As shown in Table 2, more than 26% of the study sample reported having severe depression symptoms (95% confidence interval 24.9 – 28.1) and the overall mean score on the CES-D 8 (severity of depression) was 7.4 (95% confidence interval 7.2 – 7.5). The prevalence and severity of depression symptoms was higher for females than for males.

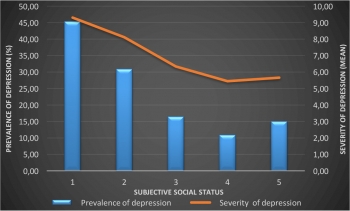

Figure 1: Depression symptoms by subjective social status

Subjective social status and depression symptoms

The study showed that there was a statistically significant relationship between subjective social status and the prevalence and severity of depression symptoms. Figure 1 shows that the prevalence and severity of depression symptoms was highest in the first quintile, representing those who saw themselves lowest on the social hierarchy scale. Those who rated themselves in the fourth quintile, recorded the lowest prevalence and severity of depression.

Subjective social status-related inequalities in depression symptoms

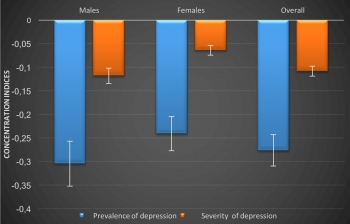

The study used Concentration Indices (CI) as a measure of inequality. The CI takes on a negative value when the outcome variable (in this case depression) is concentrated among the poor, a positive value when concentrated among the rich and a value of zero when there are no inequalities. Figure 2 shows the CIs for the prevalence and severity of depression symptoms. These were -0.276 and -0.108, respectively, indicating that depression symptoms were more concentrated among those with lower subjective social status.

Figure 2: Subjective social status-related inequalities in depression symptoms

Contributors to inequality

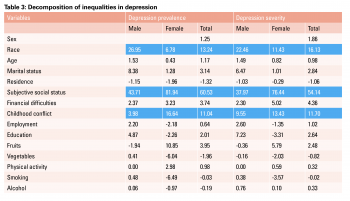

As shown in Table 3, subjective social status was the most important contributor to the prevalence and severity of depression symptoms, at 61% and 54% respectively. Other variables that made significant contributions to the prevalence and severity of depression symptoms were race (13% and 16%) and childhood conflict (11% and 12%). Table 3: Decomposition of inequalities in depression

Recommendations

Economic and social development is critical to reducing the inequalities that are related to the prevalence and severity of depressive symptoms. Mental health programmes for the diagnosis and treatment of depression should be expanded to target those of lower social status. Social protection and social welfare policies should be used to uplift those at the bottom of the social hierarchy. Our findings also suggest that interventions that target a reduction in childhood adversities are crucial to reducing depression. School-based interventions to screen for adverse childhood conditions such as conflict in the home should target affected children with appropriate mental health care and social welfare support.

Authors: Chipo Mutyambizi, a PhD intern in the HSRC’s Research Use and Impact Assessment programme and Prof. Frederik Booysen from the School of Economic and Business Sciences at the University of the Witwatersrand

cmutyambizi@hsrc.ac.za