Migrants in Cape Town - settlement patterns

Sixteen years ago, a study commissioned by the Western Cape provincial government revealed that a substantial proportion of migrants regarded Johannesburg as being over-saturated with people looking for economic opportunities. They started to settle in Cape Town, which was regarded as less competitive. Dr Stephen Rule and his colleagues looked at the 2011 Census data and other recent research, and conducted in-depth interviews with foreigners to explore the factors that guide their decisions about settlement destinations in the Western Cape.

Before 1994, most foreign migrants to the Western Cape came from the UK and Europe, but in recent decades, new streams have arrived from Zimbabwe, the DRC, Nigeria, Somalia, Bangladesh, China, India and Pakistan. However, South Africa’s migration policy has not kept pace with the changes. The 2017 White Paper on International Migration for South Africa asserts that the country has a “sovereign right to determine the admission and residence conditions for foreign nationals, in line with its national interest”. This is not fully aligned with the Global Compact for Migration (UN, July 2018), which undertakes to implement policy and legislation that factors in “different national realities, policies, priorities and requirements for entry, residence and work, in accordance with international law” (clause 15). Our research used disaggregated data to inform the development of “evidence-based migration policies”, as agreed in clause 17(j) of the UN compact.

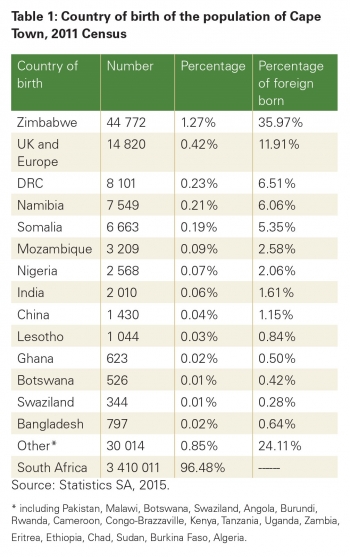

The 2011 Census data showed that 260 952 Western Cape residents were born outside South Africa, representing 12% of all migrants living in the country and 3.5% of the population of Cape Town. Their main origins are shown in Table 1

Looking at wards

The disaggregation of the 2011 Census data to ward level in Cape Town revealed the extent to which migrants from different countries had clustered spatially across the metro. The data showed that certain neighbourhoods were the homes to statistically disproportionate concentrations of people of specific national origins.

The highest proportionate concentrations of non-South African born residents were enumerated in Sea Point, Masiphumelele, Claremont, Imizamo Yethu, Green Point, Woodstock, Table View and Joe Slovo Park. The Sea Point ward had the largest proportion (17.3%) of residents who were born outside South Africa, comprising mainly migrants from Europe and the UK, Zimbabwe, Namibia, the DRC, China and India. Two other wards, the high-income suburbs of Gardens and Hout Bay had more than 1 000 residents who were born in the UK or Europe.

Eleven wards had more than 1 000 Zimbabwean-born residents. These included former white or coloured suburbs such as Brooklyn, and the more recently established settlements of Steenberg, Masiphumelele, and Imizamo Yethu in the east; Asanda, Nomzamo and Lwandle in the north; and Marconi Beam and Dunoon in the south. Namibians were mostly concentrated in Marconi Beam and Dunoon. Overall, the numbers of Namibians, Congolese and Somalians were higher than in Johannesburg, Tshwane or eThekwini.

Other more recent research corroborates and updates these patterns, as do recent confidential data pertaining to the clientele of an NGO that assists migrants and refugees. More than half (53%) of its clientele were Zimbabwean and 28% were from the DRC. The Zimbabwean clientele was spread across the inner city (Woodstock, Sea Point, CBD), the north-west coast (Table View, Milnerton), the Voortrekker Road zone (Kraaifontein, Bellville, Parow, Maitland, Goodwood), the Cape Flats (Philippi, Gugulethu, Delft, Athlone, Langa, Mitchell’s Plain, Khayelitsha), and the south peninsula (Hout Bay). Those from the DRC have settled in a similar configuration, but excluding Khayelitsha, and with an additional cluster in the southern suburbs (Wynberg).

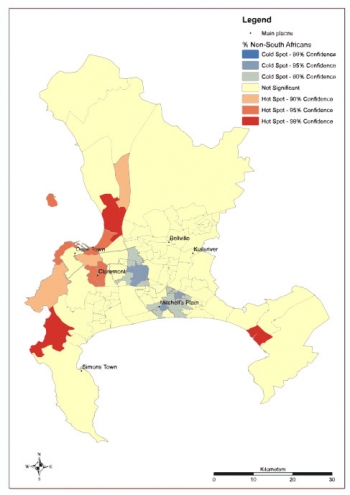

Dr Gina Weir-Smith, head of the HSRC’s geospatial analytics section in the eResearch Knowledge Centre, conducted a hotspot analysis of the 2011 data with ESRI’s geographic information system (GIS) software. She identified statistically significant (99% confidence interval) spatial clustering of migrants in the south peninsula areas of Masiphumelele and Imizamo Yethu; the north- western areas of Dunoon and Milnerton; and the eastern settlements in Strand and Lwandle. Conversely, areas of statistically low concentrations occurred around the airport and Cape Flats townships.

Highly mobile

In his paper, Dwelling Discreetly: Undocumented Migrants in Cape Town, Dr James Williams of Zayed University in Dubai wrote about the high residential mobility in Cape Town of migrants as a strategy to evade xenophobia and law enforcement. Researchers have also found that migrants’ settlement patterns are the consequence of multiple individual and household decisions related to their networks of interpersonal relations. On arrival in any foreign destination, migrants seek the comfort and safety of a residential location characterised by a cultural, ethnic, linguistic or aspirationally socio-economic affinity. Many hope to penetrate the boundaries of a precariat status, a life that is materially and psychologically unpredictable and insecure.

Xenophobia and access to transport

In Cape Town, migrants from traditional sources (Lesotho,

Mozambique, UK, Europe) tend generally to be settled in established townships and suburbs and inner-city localities. However, the new migrant streams from African and Asian countries have tended to avoid settling in the established black-majority townships, where much of the xenophobic confrontation has occurred.

Concentrations of Zimbabwean, Congolese, Malawian, Nigerian and Somalian migrants are thus most common along major intra-suburban transport routes or in newly established peripheral settlements. The suburban arterial routes offer relatively affordable accommodation

opportunities and public transport services (minibus taxis, buses, trains) and the peripheral low-income townships and informal settlements offer cheap accommodation but poor access to the economic mainstream. The two most popular major transport routes for migrants in

Cape Town are the west-east Voortrekker Road and the north-south Main Road. Although both routes have the advantage of proximity to the rail transport system, the nationally operated Metrorail is notoriously inefficient and unreliable owing to technical-capacity constraints, ageing infrastructure and rolling stock, copper cable theft and vandalism. This places greater reliance on public or private road transport options.

Looking for support

Themes that emerged from in-depth interviews with five migrant residents during 2018 were their circumstances of political and economic precarity, which served as push factors from their origins in Zimbabwe, the DRC and Burundi. Most were employed in low-paid occupations or subsistence entrepreneurial activity, and had limited or zero contact with their places of origin. Their settlement location decisions had been guided by an attraction to contexts of social or aspirational affinity, with the prospect of contiguous kinship or ethnic support systems, and anecdotal evidence of lower exposure to xenophobic sentiment. A striking story was told by a Burundian respondent who had served in an armed resistance movement, which became abusive and from which he ultimately escaped. He was pursued across five countries before reaching South Africa. Had he been caught by his army colleagues, it would have been normal practice for them to slice off his ear for not having listened to them.

He spent seven years in Durban before moving to Cape Town. All five respondents had developed networks with compatriots in churches or mutual help associations or groups with common interests. These forms of migrant networking in Cape Town are a means of engaging with, and serving as, a social-capital cushion in the context of a new, diverse, strange space or place. More explicit local government acknowledgement and accommodation of these realities would be conducive to enhancing the social and economic integration of migrants. The city would likely, in turn, reap the benefits of local economic growth and employment creation that are likely to accrue to the city. It is incumbent on politicians and urban planners to facilitate inclusive development for newcomers to the city, regardless of their origins.

Author: Dr Stephen Rule, a research director in the HSRC’s Research Use and Impact Assessment programme